Surveys

AIA Awards

DJC.COM

November 20, 2003

How the Great Fire changed Seattle's architecture

Special to the Journal

MSCUA, University of Washington Libraries, UW 7212

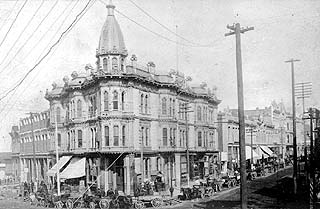

The Yesler-Leary Building was representative of downtown architecture before the Great Fire of 1889, with elaborate bay windows and cornices. It was destroyed by the blaze.

|

On June 27, 1892, fire consumed a substantial portion of the Schwabacher Building, an L-shaped structure at Commercial Street (now First Avenue South) and Yesler.

Schwabacher Brothers, drygoods merchants, suffered a reported loss of $425,000, but the fire did not spread to any other structures. This little-remembered fire was important because it showed the success of the building ordinance — and improvements to the Fire Department — that followed the Great Seattle Fire of 1889.

On June 6, 1889, the Great Fire swept over a 32-block area, virtually destroying Seattle's business core. Conflagrations of this scale were not uncommon in 19th century cities as rapid growth, widespread use of wood, lack of building codes and limited capabilities of early fire departments, made urban areas particularly vulnerable. The Chicago fire of 1871 is the most widely known, but many cities including Boston and Baltimore suffered similar fires. In the summer of 1889, fire destroyed the business districts of Seattle, Ellensburg and Spokane.

Seattle civic and business leaders faced conflicting pressures after the 1889 fire. On one hand, they needed to maintain confidence and demonstrate that the city's future was unaffected. Thus, there was a need to begin rebuilding immediately. But there was also pressure to adopt measures to provide for fire safety.

A compromise

Within a week after the Great Fire the city began work on a new building ordinance, and Council approved it on July 1. The ordinance reflected the conflicts: buildings needed to be safer (particularly to attract investors), but they also needed to be built quickly (to demonstrate that Seattle's future was unaffected).

The result was a compromise, the ordinance required structures that were less vulnerable to fire than the ones they replaced, but it did not force local designers, builders and owners to adopt the most fire-resistive technology then available.

Commercial construction at the time was load-bearing; steel frame and cladding, typical for commercial construction today, did not arrive in Seattle until the 20th century. The ordinance offered detailed requirements for the thickness and construction of walls, but made only limited mention of the framing and construction of floors.

There were no requirements for stair or shaft enclosures, although passenger elevator hoistways were to have smoke-proof enclosures. Although standpipes were required in all buildings of more than three stories, other fire-suppression equipment, such as sprinklers, were not mentioned. Fireproof construction was not required for any building.

Within the commercial district (identified as the “fire limits”), the ordinance addressed both fire safety and structural stability. Within the fire limits, walls were to be constructed of masonry with foundations at least 4 feet below grade. Walls were to be a minimum of 12 inches thick, but the lower walls of tall buildings increased in thickness depending upon height. For example, a five-story building had basement walls at least 24 inches thick, first-story walls 21 inches, second- through fourth-story walls 16 inches, and just 12 inches at the top story.

Masonry “division walls” to prevent the spread of fires in larger buildings were required and could be spaced no farther than 66 feet apart. Multiple arched openings of a limited size could be provided through the division walls. For spans longer than 27 feet, intermediate columns of iron, steel or heavy timber were required.

And, the ordinance specified the use of metal anchors to tie floor beams to the walls to reduce the chance of collapse. Other sections of the ordinance prohibited wood cornices, limited the size of bay windows, specified that partywalls must extend above roofs, required fireproof roofing materials, and addressed boilers, chimneys, flues and similar features.

Post-fire design

MSCUA, University of Washington Libraries, La Roche 2128

Post fire, new buildings along Second Avenue were designed to new code, which did away with the bay windows and cornices. Local designers were influenced by American architect H.H. Richardson. |

The typical layout of Seattle's post-fire commercial buildings clearly reflects the impact of the ordinance. A general pattern appeared in which partywalls between buildings and division walls within buildings extended from the primary street front to the alley. Where the walls were spaced farther apart than 27 feet, one or more intermediate rows of columns were introduced, almost always paralleling the walls. Floor beams 12 to 30 inches on center would typically span from the girder that ran across these columns to the walls.

For interior lots on any block, the two side walls were partywalls, shared with the adjacent buildings, and therefore completely solid, providing both a complete fire separation and also a continuous bearing wall to support the floor beams.

In downtown Seattle, lot widths usually exceeded the 27 feet specified in the ordinance, so commercial buildings were built either with a dividing wall, or more typically with one or more rows of columns from street to alley. In this configuration, the front wall at the street and the back wall at the alley typically did not carry significant floor loads because the floor beams framed into the partywalls. Therefore, the street and alley walls could have large areas of windows to bring natural light into the interior.

On corner lots the structures were more complex. Some floor framing was carried by a street wall with windows; the window openings might be limited by the need to provide adequate bearing area for the floor loads.

This was a problem addressed by the designers of almost all of Seattle's major post-fire commercial blocks as all occupied corner sites including the Pioneer Building, Burke Building, Bailey Building, New York Building, Butler Block and Seattle National Bank Building (now Interurban Building).

The major post-fire blocks typically occupied more than one downtown lot. Buildings occupying two lots were typically 120 feet in width. As downtown lots were also about 100 feet in depth, these large blocks required internal masonry firewalls since the ordinance required such walls no more than 66 feet apart. Designers of Seattle's new large business blocks incorporated these “division walls” extending from the street to the alley. These walls can still be seen in the surviving larger post-fire buildings in Pioneer Square.

The relative ornamental restraint of Seattle buildings after the fire was fostered, at least in part, by the new building ordinance. Elaborate wood cornices of pre-fire construction were not allowed and bay windows, which had been typical in pre-fire buildings, were limited in size. So the ordinance presented a challenge to Seattle's architectural designers: to find an appropriate architectural language for the design of masonry commercial architecture within the constraints of the ordinance.

In this context, Seattle architects' decision to follow the example of the well-known American architect H.H. Richardson, and their choice of Romanesque Revival, may have been the logical result of a search for an aesthetic approach that could guide design under the new constraints, and not simply an arbitrary stylistic decision.

This essay is adapted from the recently published “Distant Corner: Seattle Architects and the Legacy of H. H. Richardson” by Jeffrey Karl Ochsner and Dennis Alan Anderson (University of Washington Press, 2003).

Other Stories:

- Today's buildings load up on technology

- Monorail to move urban design as well as people

- Letting rainwater reign in the design process

- Church praises the benefits of adaptive re-use

- UW builds on design leadership training

- Science studies how architecture affects the brain

- China creates a park with environmental appeal

- Architects play catch-up in the business world

- Designing with nature in the balance

- 12 keys to creating authentic people places

- Water tower repairs borrow on building technology

- Technology takes center stage in performance halls

- In hospitals, spending more can save money

- Don't be violated — protect plans with copyrights

- Special dampers may shake up engineering field

- UW Allen Center fosters a culture of research

- Here's why projects need to be commissioned

- Unwrapping modern building envelopes

- Lessons on sustainability, Scandinavian style

- Building a highrise on the fault line

- How to keep development from killing trees

- Rx for changing healthcare industry: Good design

- Muckleshoot project blends culture with design

Copyright ©2009 Seattle Daily Journal and DJC.COM.

Comments? Questions? Contact us.